FOCUS: Philadelphia; 'Old City' Stirring With Life

THE Chocolate Works looms, large and Victorian, on one corner of the Philadelphia neighborhood known as Old City. On another corner sits Smythe's Stores with a handsome, cast-iron facade. Still another block features the Castings, a collection of industrial buildings dating from the 1700's that until recently was a foundry.

Block after block of the historic community along the Delaware River contains recently rehabilitated warehouses and factories.

In the last five years, more than 900 rental apartments have been carved out of former commercial structures, creating in the process an almost entirely new residential neighborhood.

For decades, the only residential area of Old City was Elfreth's Alley, the oldest continually inhabitated street in the United States. In 1970 the census found 80 residents of Old City. By 1980 the figure had increased to 300 and it is now put at close to 2,200.

The situation in Philadelphia is far from unique. Stimulated by tax breaks, hundreds of companies across the country have redeveloped 11,700 historic buildings since 1982, according to statistics from the National Trust for Historic Preservation. Altogether, the total investment in historic properties has been $8.8 billion.

But Philadelphia has perhaps enjoyed the most concentrated burst of such development. Hundreds of buildings have been rejuvenated - many of them in Old City.

In the 1970's, Old City ''was an interesting and viable neighborhood,'' said William A. Kingsley, president of the Old City Civic Association. ''It was mostly wholesale, with some small manufacturing.'' Today, the area has a new element. ''Talk about yuppiedom,'' Mr. Kingsley said. ''In a survey we did of Old City residents, we found that more than 50 percent of the people had postgraduate degrees, the median age for men was 36 and for women, 33. Half of the household incomes were above $50,000.''

Although some developers talk of a soften-ing of the market for high-priced rental apartments - charges are approaching $1 a square foot per month, steep by Philadelphia standards - it appears that building activity in Old City is as furious as ever.

Construction crews are finishing the 135-unit Chocolate Works at 231 North Third Street and the 165-apartment Bridgeview at 315 New Street, two projects of Historic Landmarks for Living, a Philadelphia-based company and the largest historic rehabilitation company in the country.

The Castings, a 61-apartment building being developed by the American Classic Development Company on Quarry Street, is scheduled for opening late this fall. And the Devoe Group, another local company, has about 75 new apartments, including the Smythe Stores at Front and Arch Streets.

Old City, which extends from Race to Walnut Streets and from the Delaware River to Fifth Street, once was Philadelphia's center.

In the 1800's, however, businesses such as banks and retail stores and the residential population began to move west. At this point, Old City became a district of warehouses and light-manufacturing plants, with streets filled with four- and five-story buildings.

Planners say Old City never seriously suffered the heavy urban blight that rolled through many of the country's manufacturing districts. ''There were not many vacant properties,'' said Warren E. Huff, the Center City planner for the Philadelphia Planning Commission. ''But they were certainly underused.'' Interest began to focus on Old City as a possible residential area in the early 1970's. Artists seeking large and cheap living and working spaces found the old warehouse buildings perfect. Rents then were about 40 cents a square foot per month, or about $300.

By 1975, the city Planning Commission had studied Old City, ''looking at the potential of almost each and every building,'' Mr. Huff said.

Soon people like Stephen E. Solms, a developer who is the chairman and founder of Historic Landmarks for Living, ''started walking around the streets down there.''

''I thought, 'This is like SoHo,' '' said Mr. Solms, whose company now operates in seven states. ''This reminds me of New York.''

At the same time, the Federal Government instituted the Investment Tax Credit, which provided for accelerated depreciation on historically certified structures that were restored. In 1981, the Government strengthened the legislation, providing 25 percent tax credits in addition to the accelerated depreciation. In doing so it created a historic rehabilitation industry.

Although the rehabilitators of historic properties have suffered through almost three years of uncertainty about the status of their tax credits, as the Reagan Administration and Congress have debated new tax legislation, analysts say it appears as though the credits have been preserved.

IN 1982, Historic Landmarks started its first large project, the 97-unit Wireworks.

''It proved to be a major stimulus to development in Old City,'' said Carl E. Dranoff, president of Historic Landmarks. ''It brought in critical mass.''

Since then, Historic Landmarks has developed nine buildings in Old City, including the complex called Bank Street Court at 24-26 South Bank Street. Many others followed.

One, the Devoe Group, headed by Harry Devoe, has developed three properties in Old City. ''Mr. Devoe came in after Historic Landmarks and they've proven to be his biggest competitors,'' said Cynthia O. Hillsley, the vice president of the Devoe Group.

Florence Rosen, president of American Classic Development Company, said she did her first Old City building, the Chocolate Factory, in 1983. She said she was attracted to the area ''because it is always different.''

''There are new types of buildings,'' she said. ''History comes alive for you.''

While the area still has that excitement, some developers are beginning to talk of a slowdown in the rental market and in the development potential of Old City. The number of buildings suitable for large-scale restoration has declined dramatically, Mr. Dranoff of Historic Landmarks said.

And Mrs. Hillsley of the Devoe Group said that while the rental market ''will not dry up,'' the developers in Old City have to be aware of the ''decline in the yuppie population that started about five years ago.''

''The prospective residents are getting street smart,'' she continued. ''They want to know 'what can you do for me?' ''

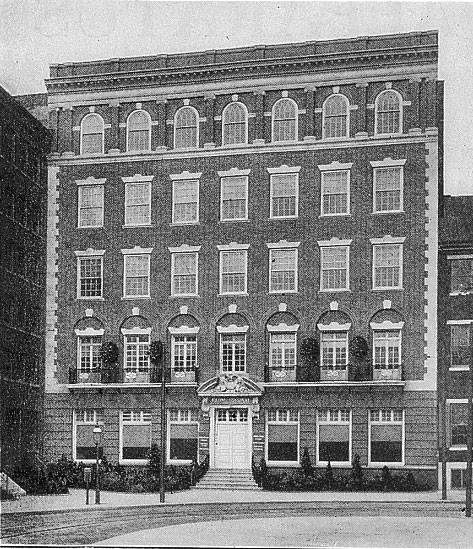

Smythe Stores 100 block Arch St

The Castings 140 N Bread St

Smythe Stores 100 block Arch St

The Castings 140 N Bread St